I like to say that “Scientists want to understand how the world works; engineers just want to get paid.” It’s a gross (but funny) over-simplification. Engineers must understand an enormous amount of details to: build a better engine, handle water planning for a city, build a control system or chemical plant. Engineers experiment: they just have goals in mind for how to use the knowledge.

At the game club during grad school, the people playing were skipping classes from a variety of degrees: Scientists, Engineers, Mathematicians, and even some Liberal Arts majors. But for a few months we could at least pretend our games were not modeling wars, or trains, or aliens conquering planets; but a simulation of the scientific method itself.

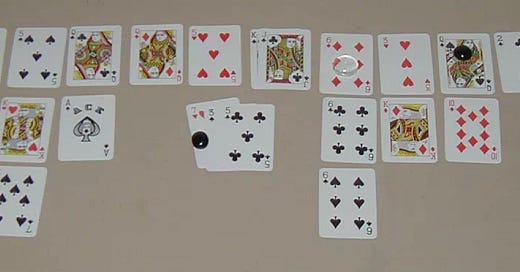

Robert Abbott’s Eleusis is a game about discovering the rules. Or — more accurately — the rule. In some ways its a shedding game: get rid of your hand of cards. But when you play a card (or more than one) they must follow a rule that you don’t know. The dealer (called “God” or “Nature”) creates a rule, such as “If the prior card was Red, the next card must be higher. If it was black, the next card must be lower” and flips up the first card.

When you play a card and it “follows the rule” it goes to the right and you’ve got one less card to deal with. If it doesn’t, it goes below the card, and you get penalty cards. First one to go out wins.

There’s more, including allowing a player to become the “Prophet” who answers whether the rule is correct (confirmed or not by the dealer) and scoring so that you play multiple hands (so that everyone can play God). 1

For several months, we played Eleusis. We weren’t just skipping classes, we were “exploring the scientific method.” Perhaps not in the way that Abbott intended.

One of the great debates in science is the Argument From Elegance (or beauty). There’s no reason why the universe’s rules have to be mathematically elegant — but they often are. Electromagnetics? Four equations. Laws of Motion? Newton’s three laws. You get the idea.2

Initially, our rules were elegant. But in our hearts, we’re gamers first and scientists/engineers/whatever second. (See also, “skipping class”). We wanted to win, and exploring the rule was secondary. Rules were made that contained traps for the prophets, inelegant edge cases. Was that a suicide king? A one-eyed jack? Did the prior three cards form a flush?3

We were following the scientific method; but also the 20th Century’s March of Science where Newton’s laws were supplemented by relativity and Atomic Theory was shown to have level upon level below it. So in one way, Eleusis works on that level, too.

But by then we had quietly moved on.

It may that we weren’t the target audience. Eleusis has been re-jiggered as a pedagogical teaching tool (simplifying the rules for school children). Kory Heath and Andrew Loony, made an excellent Eleusis variant called Zendo that uses Loony Lab’s “Icehouse” pieces instead of cards4. Similar gameplay, excellent aesthetics.5

Also related is the card game Mao, another card game involving shedding. I personally consider Mao more prank than game. Mao’s rules vary wildly by groups, but the big difference is that each hand does not have new rules. Mao has lots of rules that new players have to learn — teaching them is obviously against the rules6 — but once you know that group’s rules, you are done.

But the big question — Does Eleusis count as one of the 100 Most Influential Games of the 20th century? I must admit that I’m torn. I greatly admire any game with pedagogical value, particularly when what it teaches is so important. And the fact that Eleusis works as a game for kids or gamer engineers — at least for a while — is impressive. Many great games have limited replay value, just consider legacy games or InfoCom puzzle computer games, so I don’t think that should be an issue.

My hesitancy may stem from the fact that the Eleusis branch of the gaming tree is so sparse, with few offspring, and even the offspring seem endangered. Right now I think that Robert Abbott’s creation is on the cusp of making the cut. It might get in, but I’m not positive.

The Eleusis Wikipedia page has a nice summary if you want the full rules.

Chemistry can take a long walk off a short pier, as far as I’m concerned. Sure the equations have to balance; but that’s stolen from conservation of mass.

Later rules started referencing things besides the cards, like how many markers were on the board, which is probably against the meta-rules.

First introduced in “Icehouse,” which I think I also first encountered in grad school. But nowadays there are dozens (hundreds?) of games that can be played using those cool little pyramids, sometimes referred to as “Loony Pyramids.”

If Zendo had been published before 2001, instead of during 2001, then we’d have to decide on a joint award. But since it was; we don’t.

Hence, a prank. Or hazing. Good natured, presumably, but still.