Wargaming has always been popular, and around since Kriegsspiel1, if not earlier. One of the most difficult aspects of properly handling war is dealing with Fog of War. For a single battle modeled by Kriegsspiel and successors, you could hand wave away such issues. Even in the Napoleonic era a commander would have a reasonable idea of the troops for both sides and their placements prior to the battle; although who knew what reserves might be nearby or hiding in the woods?

But as wargames got more complex (and became more game than tool for professional soldier), battles gave way to fronts or entire conflicts. While Napoleon or Bay or Grant might be able to survey the battlefield, nations struggle to figure out where all their own troops were during a conflict, much less the enemy! The “God’s-eye-view” that many games provide was unrealistic.

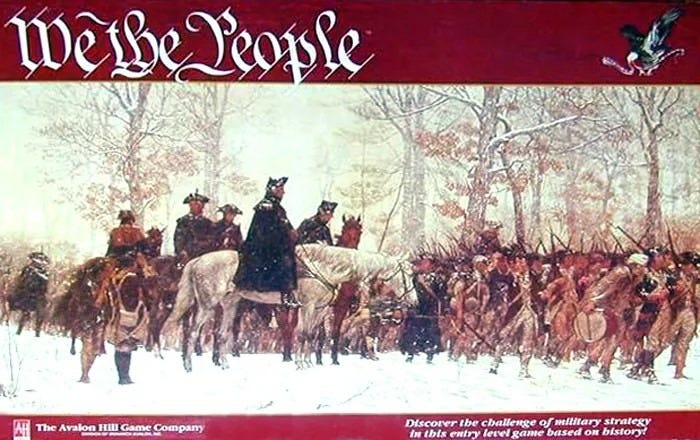

Mark Herman tackled that problem — and others — with We the People.

We the People is the first “Card Driven Wargame,” sometimes called CDG2. So Fog of War isn’t represented on the board — both the British and American players know where all the generals and armies are. But you didn’t know what your opponent could do with those forces. In CDGs, cards can be played for operations. In We the People, generals have a rating, and the better generals could be activated by more cards.

So a menacing stack of armies commanded by a poor leader may be a paper tiger with the wrong hand of cards. Not only did this card driven system provide fog of war, it also provided a more realistic command and control system. You — the player with the omnipotent view — knew that you could crush the enemy. But your general can’t or won’t do it, because you lack the cards.

Armies are not Chess pieces obediently moving on demand.

Cards could also be played ad events, which may allow for surprise reinforcements (or losses due to weather), multi-army campaign movements, political shenanigans, or the like.

We the People’s system was quickly recognized in that it created a riveting, fluid game play. Wargamers love the “What-if” question and one of the issues with (non-referred) wargames is that the rules must be defined in advance. In many games, you know that your opponent’s exact capabilities. Not so in a CDG. Even the battle system removed dice. In earlier wargames if you outnumber your opponent by six-to-one (or whatever) it’s an automatic win, but in We the People you just get more cards in a small battle game. The exact odds are probably calculable, but not by most people.

Almost nothing is ‘automatic.’ Sometimes players would snatch defeat from the jaws of victory because of their fear of what an opponent could do, or salvage a seemingly hopeless situation because your opponent was unprepared.

(Just like real wars).

We the People is still played today, but its true legacy is “the first CDG.” Soon games used the system to explore perennial wargame favorites like the Civil War (For the People) and World War II (Empire of the Sun and WW2:Barbarossa to Berlin). But any conflict is more amenable to simulation when special cases can by handled by individual cards. Developers soon extended CDGs to cover conflicts not often seen in “traditional” wargames, such as:

Twilight Struggle covers the Cold War and was the highest rated game (of any genre) on BoardGameGeek for roughly five years.

Paths of Glory covers the first World War, and is widely considered the premier CDG. It was also released in ‘99, which makes it eligible as well!

Here I Stand sees the Papacy fighting against Reformation, with other European Powers (and the Ottomans) in the mix.

Despite the ‘simplification’ that event cards allow, many CDGs are much more complex than We the People’s relatively simple system3.

While I don’t consider We the People a first ballot entry in the 20th Century project, I do consider it a definite inclusion: A wargame that still sees (some) play today that spawned a genre that is thriving three decades later. But I do understand that there is some room for debate, particularly in replacing We the People with Paths of Glory.

A Note on the Project

I am not writing these articles in any particular order. This means that I have not finished with all the “first ballot” games and moved onto the next tier. While I do have a list, I am writing them more in “the order I fancy.” (I have several obvious inclusions that I find I have little to say about).

I also plan on writing up entries on (many) borderline games, which are probably the more interesting cases to debate.

Readers may note that I go into slightly more detail in gameplay in this article. These are not meant to be reviews or descriptions of mechanisms (plenty of those are already on the Internet), but as I move into more ‘niche’ games some descriptions must be provided to explain why I feel the game is worthy of inclusion (or at least consideration) into the 20th Century Project.

Guest authors are certainly welcome. There are certainly games that I know about that I can say little of interest, so if you want to submit an essay for a game, please let me know.

Also — Check out Joe Huber’s article on The 50 Most Historically Significant Games Published since 1800.

If videos are more your thing, see this history of Kriegsspiel

I guess the “War” is silent.

The Box itself proclaims We the People is an “entry level” wargame.